Klan Country

A Novel in Progress

“Ah, the family,” she said, releasing her breath and sitting back quietly, “the whole hideous institution should be wiped from the face of the earth. It is the root of all human wrongs,” she ended and relaxed, and her face became calm. She was trembling.

—Katherine Anne Porter, “Old Mortality”

I

Once more it was five before nine on a Saturday morning (this one in May, five days after Kent State) and once more, as punctual as the sun, my Grandfather Woodall stood white-haired and erect on the brick pavement beside the Old Well, his blue gaze fixed across Cameron Avenue and down the wide brick walkway that ran between South Building and the Playmakers Theater. From my window high in Old East (a window shut still, out of shame shut still, though it was warm outside, warm as July), I could look down and see him from the rear: tall and elegant in his tailored and pressed salt-and-pepper suit, his black dress shoes polished as mirrors, his neat, gray Homburg held out with both veined hands in front of him, close over his waist.

Standing so, arrayed so, his stage set that little, round Vesta-temple with the Doric columns and copper dome and wrought-iron drinking fountain in the center, he reminded me of a Confederate general in retirement, posing for a photograph—an Early or an Anderson or a Longstreet in one of his Freeman books back in Raleigh. I squinted hard from my shut window and for a sudden, aching wave in my chest, could see—believe!—I wasn’t up here, in this closed, overwarm room, tie wretchedly askew, dress shoes scuffed, shirt and trousers rumpled like a street drunk’s, every pore of me sweating and stinking, shit smell and semen smell welling up out of my crotch like a grim mist, some strange college boy’s semen sticky as rotten glue on the roof of my mouth. No, I was down there, once more crossing Cameron and striding straight to him over the antique brick, dressed neat in the dark, pressed trousers, the white, starched long-sleeved shirt and dark tie, the dress shoes as black and mirror-polished as his own, in my left hand gripped the big, black brief case he’d presented me for my high school graduation in June ’66. And all through my striding to him (so I heard—believed!) ran in my mind the verses from the Fourth Georgic I’d just translated (and memorized) in Dr. Applewhite’s Virgil class—verses poised to spring from my lips, in not quite theatrical orotundity, the moment I stopped before him and reached out to grip his proffered hand.

I shut my eyes and could see—believe!—how it would go between us in the four hours following: how, hard upon our ritual grip and my verses from Virgil, he’d intone his own mock-solemn, “Si vales, valeo; bonum est,” and then, clearing his throat, as if about to give a speech, ask once more: Would I accompany him “this fine morning” (even if it were raining or overcast, it would ever be fine—“a fine morning”) down to “Klan Country” (“Heh, heh, heh,” he’d be sure to utter) and the old Woodall homeplace, “seat” of his father’s father and my “distaff side”? As I was “well cognizant,” his brother, my great-uncle Merrick, had put it up for sale at last, and he, “this old Dee-di” of mine, eighty-one and retired for good, away at last from “the consumptives” and the X-rays and all the weekly traveling—he, “an old widower of leisure now,” with no salaried employment or “future prospects thereof,” had “purposed” to purchase “said seat” and in his “hiemal years” restore it to its “antebellum state.” He’d perform “the light labor” himself, whatever little painting and repair “this old carcass” could accomplish. The remainder he’d commission to contractors: the new foundation and new roof and the filling of the columns eaten hollow and much more than he could name just now, my “old forgetful Dee-di.” Would I “therefore”—I, his only grandson and “sole male sustainer” of the Woodall line (my uncle had two daughters “merely” and, at 33, mumps had “rendered him sterile”)—would I go down with him “this fine Saturday” and meet my great-uncle Merrick there? (Grandfather had telephoned him we’d meet him at one, “on the lower veranda.”) If we left now, we’d have the leisure to stop by Rosewood and see Mrs. Loreena Wooten, a widow herself and his “future helpmeet.” And we’d have time to walk the Bentonville battleground and tour Ava Gardner’s schoolhouse and teacherage—and even visit the old clapboard church my great-great-grandfather (“Union Man that he was, yessir,”) had built “for the colored people.” Of course, he’d drive me himself, “with all due pleasure, Dr. Lockhart.”

I opened my eyes and looked down at him, and from his steady head, his stance so willfully still he seemed nearly to tremble, I knew he was playing it all through to the end, in a mind’s eye keen and fatalistic: how it had gone between us every Saturday since the twenty-eighth of March (he’d first arrived at my dorm room on the twenty-first, with no warning, not even a phone call) and how surely it would go between us again today, “this fine morning”: how the word “pleasure” would have barely come out of his mouth when I’d have said, in that aloof, resonant professor’s voice (which already infected me then and often infects me still—even on stage—twenty-six years later): I “deeply” apologized, but I could not accompany him “just yet”—not today at least. I had another examination for which to study—my Latin comprehensives—and a “lengthy paper”—this one on the Georgics. And that night (and I’d have been sure to say this with a wink, sly and conspiratorial), I’d made “a prior engagement”—with a “Linda Maupin” or a Teresa Cheshire” or an “Elaine Trentman”—whatever old-Raleigh, blue-blood name would have emerged in my mind just then. (Of course, I was lying about the “prior engagement,” as I’d been lying about it the six Saturdays previous.) But—I’d have gone on—“my schedule” would permit an hour for “light luncheon,” perhaps at Harry’s downtown.

And then he, his voice going tight and clipped, like that of the Army Medical Corps colonel he’d been for thirty years—his first career, long ago—this narrowed voice the only sign of his (I knew) deep disappointment: “That will be satisfactory, sir. We shall drive to the homeplace on a Saturday forthcoming. I shall telephone your great-uncle Merrick not to expect us today. He has long advertised for the sale but has assured me by certified letter, in accordance with my request, that he shall not first negotiate with another party other than myself.” Here he would have raised a hand from the brim of the Homburg he held, touched forefinger to thumb, and gone on, “Of course, I know—and you, likely, as well, Dr. Lockhart—how large a salis granum his word’s been worth. But after all these years—Lord, I haven’t seen him in twenty!—he may have changed. People do change, you know. Just give ’em time, yessir, and they change—most people, anyway.”

Then, setting the Homburg on his head, straightening it just so, he’d have bowed slightly and said, with no trace of irony, his voice broadening back, “So I shall lunch with you at noon, Dr. Lockhart—at your Harry’s downtown. Meanwhile, to pass the morning profitably, I shall visit the North Carolina Collection and there peruse, with interest, your great-great-grandfather’s letters to Governor Zebulon Baird Vance and President Ulysses Simpson Grant.”

In the three hours following, while he’d have “perused” among the faded and brittle sheets of foolscap, I’d have returned with the briefcase to my overwarm room, ,taken the Oxford Vergili Opera and the Cassell’s New Latin Dictionary out of the briefcase and set them side by side on my desk. I’d have then opened the Vergili Opera to the Fourth Georgic and bookmarked it with a cheap Bic. Then, setting the briefcase by the bureau dresser, I’d have desultorily swept and dusted, changed my soiled and wrinkled bedsheets, and taken a brief nap on the coolness of the freshly laundered ones.

At noon precisely we, the two of us, would’ve been seated across from each other in a cramped, stuffing-sprouted booth in smoky Harry’s, and over the hour there—not a second longer or less—Grandfather would have slapped down onto the stained Formica the enlarged, cracked, yellowed black-and-white photograph of an antebellum façade, the old Woodall homeplace, to be sure: the window shutters missing, the panes cracked and broken, the now-wooden porch steps black-weathered and sagging, and the far-right column gone from the lower portico, replaced by an old creosote pole twice as thick as the remaining columns—which were white still, though chipped and splintered in places. Over the whole façade, the paint was peeling everywhere, like the truck of an old sycamore.

Without touching the steak sandwich Grandfather had ordered, he’d have regaled me once more with the statistics and facts of the old house and the Civil War anecdotes of events rumored to have taken place there: how the “Federals” had dumped dead chickens onto Mrs. Woodall’s grand piano and how the fellow-Mason Federal officer, ordered to “fire” the house, had refused to do so when he saw the Masonic emblem hanging above the parlor mantelpiece, and on and on ad nauseam: tales I’d heard from him since I was five or six—“history,” Grandfather called them. And all the while his face would have been flushed deeply, his voice oddly breathless and manic, now and then breaking high and hoarse, like an excited boy’s.

Then, the anecdotes finished, Grandfather would have slapped down another photo, also black-and-white but smaller and much more recent. It showed the face and neck of a handsome woman—in her midfifties, maybe—her (no doubt, dyed) dark hair styled in the high, Jackie Kennedy bouffant hairdo so popular in the sixties. Even in middle age, she had the bright eyes, the fine, straight noise, the full lips, and the high cheekbones of the beauty queen she had been—“crowned Miss Goldsboro back in 1931.” “And this feminam pulcherrimam, Dr. Lockhart—Mrs. Loreena Wooten,” he’d have said, “it is my intention to wed, once the homeplace is mine and its interior has grown fit for her presence. When we drive down to the homeplace on a future Saturday, I’ll take you to meet her, just outside Rosewood. Oh, you wouldn’t believe all her talents—photography, painting, sculpture, gardening—and more—Lord, I can’t keep count of ’em! And she’s always been so nice to me—so eager to see me. She’s out the X-ray trailer door before I can even get out of the car!” And on and on the old man would have rambled, rolling out nearly the same words I’d heard from him in Harry’s the six Saturdays previous.

Of course, all the while I’d have been spooning up my watery chowder in quick slurps, wolfing the underdone Reuben sandwich, gulping down the Mason jar of oversweetened iced tea, glancing covertly at my wristwatch, in torment for us to quit that smoke-hazed place and walk back across campus—him to his old white Chrysler, me to the clear still of my room, the Fourth Georgic open on my desk, the cheap Bic gripped in my right hand and poised above a sheet of legal pad. Grandfather would have taken a sip from his own Mason jar of oversweetened iced tea and then a bite out of his steak sandwich, chewing it slowly. Then he would have covered his mouth with his hand, cleared his throat long and loud, as if he were about to give a speech, and said—words I remembered verbatim from the letter he’d sent me seven Saturdays ago:

I recognize that some of the family will object loudly to my enterprises—your mother and your uncle Claude, especially. In fact, I can already hear them: “What? An eighty-year-old man living out there—in the country? And living there all by himself? And in that house in its condition? And with no central heat? Why, he’ll catch double pneumonia, just like his own mother in that drafty old house in Goldsboro. And remarrying at his age—and this common Loreena person at that?” And on and on and on, the same sort of shrill complaints which I heard your grandmother whine for over forty years—and which now, in my old age, I no longer wish to endure. Hence, I ask you, Dr. Lockhart, that you keep my two new enterprises confidential, at least until the sale of that grandeur is accomplished, at which time I shall write your mother and uncle and shall all reveal and at length.

Just so I yearned for it all—oddly, even the parts I resented—to come round again as I stood that Saturday morning in May behind my shut window high in Old East, gazing down at him so grand and erect beside the Old Well, the nine-o’clock sun just now brimming over the Playmakers pediment and glowing him full—from his silver crown to the shining black tips of his shoes.

In fact, a little over an hour ago, just as I stepped outside the dormitory, lugging the briefcase into the cool shadow of the quadrangle, I foresaw clear as a movie the whole Saturday ritual. And I intended to play it through once more. I saw no reason on earth to do any different.

But a few yards down the brick walkway, I noticed the quadrangle all silent but for sparrows chirping under eaves, and I raised my head from its accustomed stoop and saw not one of the dozens of students morose, disheveled, sullen-eyed—sauntering resentfully to their Saturday classes in Saunders or Bingham or Murphy or Dey. Only I was in this place, hearing my long, pounding strides.

I crossed Cameron, strode between the Playmakers and South Building, and came out into the larger, sun-splashed quadrangle, the great, white portico of Wilson Library shining far ahead of me. This place, too, was all empty. Just squirrels were there, scurrying up thick oak trunks, and robins pecked in the grass and among the thick claws of the oak roots.

I hurried past a sign—it caught my eye: a large square of white-painted plywood nailed to a stake driven into the ground. I stopped and swung around and strode back to it and stopped and stooped and, gripping the briefcase still, read the black-painted capitals, printed slightly askew. I pored slowly, slowly over them, and I read them slowly once more, as if they held me under a spell:

RALLY FOR PEACE!!!!

MCCORKLE PLACE AND FRANKLIN STREET

SHARP NOON SATURDAY MAY 9

SPEAKERS: ROBBIE BELLO STUDENT BODY PRESIDENT

AND MAYBE ABBIE HOFFMAN!!!!

COME HONOR OUR FALLEN COMRADES

KENT STATE MAY 4, 1970

A DAY THAT SHALL “LIVE IN INFAMY”!!!!

LONG LIVE THE REVOLUTION!!!!

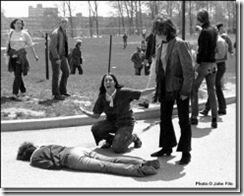

Under the skewed capitals was tacked a dim, grainy photograph torn raggedly out of a newspaper. It showed a girl, seventeen or eighteen, dressed in dark pants, a dark blouse with sleeves to the elbows, a light-colored kerchief tied loosely around her neck. Her long dark hair was swept back to show a high clear forehead. She was kneeling on a street pavement, her slender white arms stretched out in front of her. Her mouth was open wide, as if she were yelling, shrieking, weeping—I couldn’t tell. She faced the body of a young man stretched out limp on his stomach, an arm stiff-straight down his side, his face twisted away from the camera, cheek firm on the pavement. He was dressed in dark jeans and a light-colored windbreaker, and his thick dark hair, mashed by the pavement, was bunched high around his head. From the other side of him—some torn place I couldn’t see—a thin dark stream—blood, I knew—ran twisting over the pavement and between the girl’s bent knees and on behind her, gathering in a ragged puddle at the curbside. To the right of the two of them stood a neatly long-haired young man in a worn, light-colored blazer, an open-collared shirt, and bell-bottom jeans and boots. His face was twisted away from them, staring bewildered into the distance. Beyond the three stretched flat ground and a high chain-link fence and then the flat ground again. Students were milling about, as bewildered as the one in the blazer and bell-bottoms. Some were gazing beyond the fence—at the retreating soldiers of the National Guard (I later learned). But most were gazing numbly at the dead boy, the grieving girl.

That clipped photograph I’d already seen but taken spare notice of. Just Wednesday afternoon, my roommate Victor Katz had slapped it hard on my desk, covering my open Fourth Georgic over which I’d been dutifully bent. Then he’d fairly screamed at me, in that self-righteous, “activist” shrill I found so irritating, “And here you can read Vir-gil [he’d spat out the g as if it were something rotten] when they’re murdering kids! Shame on you, Lockhart Titus! Shame! Shame! Shame! But at least you can redeem your prissy self, ’cause we’re rallying on Franklin tonight—and marching—permit or no permit. Let ’em cram us all in the paddy wagon—who gives a flying fuck? Anyway, you be down there, hear? Franklin and McCorkle. Eight sharp!” And before I could finish my usual, “I’m so sorry, but I’m due for a major exam tomorrow,” he’d spat, “Due—I know—like having a goddamn baby—and a re-tard at that! Fuck it!” And he’d whipped around and burst out of our room, slamming the door so hard behind him his framed Easy Rider poster (Dennis Hopper glaring from a Harley) dropped to the floor, splintering glass all the way out from under his bed. (I knew he’d just yell, “Fuck it!” when he got back and then sweep up the glass and roll up the poster and cardboard backing and dump it all into the trash barrel in the hallway and forget about it. “It’s just a thing!” he’d mutter: “Un-im-por-tant.”) But then, after the door slammed, the glass splinters inches from my feet, I could hear his big boots pounding down the hall, then fading as the stairwell door slammed shut. When there was quiet again, I merely glanced at the clipped photo, without seeing it, and whisper-sighed wearily, like a resigned old man, “It’s just not you, Lock—not your way, your life.” Then I tossed the photo flat into the waste basket beside my desk and hunched once more, dutifully—yet, deep inside, ruefully—over the Fourth Georgic.

About “that war” I had no opinion one way or the other. It was some far-away “foreign matter” that had no connection to me at all—other than the bothersome steps (I knew not what) I’d have to take to extend my draft deferment in June, or somehow get classified 4-F. In those tunnel-mirrored days, I was just a classics scholar, my mind set on summa cum laude and then graduate school at Princeton, where I’d already been accepted. Besides, I loathed—and shunned—loud, cursing “demonstrators,” especially the scruffy, long-haired “revolutionaries” with their self-righteous slogans and abrasive voices and megaphones and crudely hand-lettered posters and chanting rallies along Franklin Street.

But why hadn’t I asked Victor to move out long ago? Or why hadn’t I moved out myself and rented a cheap room in an old widow’s bungalow? For ever since we’d begun to room together, the first day of our freshman year (we’d been thrown together by lottery), I’d found him that loud, scruffy, self-righteous type I couldn’t bear. And day after day I’d had to hear him scold me in that shrill, quarrelsome way of his—for my “aloof prissiness.” Hearing him, how I’d winced with irritation inside!

But—oddly for an “activist” sort (who’d usually major in Political Science or Sociology or even Religion)—he held a very different ambition, a passion that had fiercely attracted me, in grade school and high school, and that attracted me now, a vocation for theater—for six years now my secret love, my mere fantasy-calling. A drama major, he played the leads, always the leads, in student productions—Dionysus, Orestes, Hamlet, Stanley in Streetcar, and more—all those roles so much like him: radiant with a dark and angry vitality.

And yes (and of this I was only vaguely, shamefully aware), he held other charms englowed with the first: the full sensuous lips, the straight white teeth revealed in a startling grin (rare) or a taut grimace (more often), the handsome, east-Mediterranean molding of his face, the high, thick, black curly hair, the wide, lake-brown eyes ever staring, ever piercing me, and, above all, the defined chest muscles under his T-shirts. (After rising, he did push-ups every morning, without fail.) So whenever we’d finished a falling out over my “aloof prissiness,” I’d squirm with resentment the whole night afterward and decide “with finality” to say to him next day (I’d even memorized the lines): “I’m terribly sorry, Victor, but this isn’t working out—our rooming together. Would you find another place to stay? I’ll help you search—help you move, even.” But next morning, in early dark, in the dim light of the desk lamp, I’d be bent wide-eyed and dry-mouthed over him as he slept on his back in his rumpled bed, that high shock of curly black hair spread over his coffee-stained pillow, that chest naked, hairy, defined and, when the heat was too high, coiled with the threads and tiny beads of his sweat, and I’d feel myself harden—fiercely, painfully—and so relent and “forget” to bring up “the subject” in the few minutes we gulped coffee together before rushing off to classes.

So, yes, I’d seen that photo Wednesday afternoon, and three days later, on that Saturday morning in May, a little past eight o’clock, I saw it again, tacked to the plywood sign, under the rally announcement. I was about to stride on—I was late for class—but found I couldn’t take my eyes off the kneeling girl, the shocked grief in her open mouth and outstretched arms. It came to me suddenly she was weeping in that deep, wrenched, down-in-the-lungs way I’d only—so far—heard once in my life, dredged up painfully out of myself, years ago, in circumstances that, at twenty-two, I’d long damped from memory. I gazed at her a while longer, shuddered violently, then shook my head to steady myself and swung around and strode on, faster now, over the antique brick and then, taking two at a time, up the broad stair steps of Murphy Hall and through the double swinging doors and into the small, bare vestibule. I glanced at the restroom’s double doors to my left, shook my head sharply, then lunged through a second pair of swinging doors and into the corridor and stopped, the gripped black briefcase a great weight by my side. This place, too, was empty, like the campus, and I slowed, as if entering a church, and heard my footsteps echoing. When I entered Room 204, my vast, high-ceilinged Virgil room (much too large for a class of twelve students), I saw empty school desks in neat rows and, on the blackboard, a note in Dr. Applewhite’s neat cursive, “Out of respect for the Kent State fallen, once again no class shall be conducted today. For Tuesday, May 12 (we shall meet then), translate the next fifty lines of the Fourth Georgic.”

I scanned the rows of empty desks, heard a sharp clank from a cooling radiator, then saw in my mind the grieving girl from the photograph. My stomach fell as I felt for the first time in five years (an eternity when you are twenty-two) how lonely my life was and how utterly deep a lonesomeness it had been. I remembered how, for four years nearly, I’d lived only for my cramped routine: the striding to classes, the hunched studying over the scratched, wobbly table I called “the desk,” the occasional yet ever formal, cerebral conversations with Victor over our gulps of morning coffee, the rushed, solitary meals at Lenoir Hall and the Carolina Inn, and, in the summers, (yes, summers even—what might have been bright, carefree, Frisbee-flinging Junes, Julys, Augusts, or, better, enlivening work outdoors, as a camp counselor, perhaps) my lonely job at Wilson Library: shelving books, filing cards in narrow drawers, steering by their cool, bony wrists bespectacled, owl-eyed old ladies into the stacks—to their adored books they could barely read, much less see to find. As I stood in that vast, silent classroom, I saw the past four years (except for rare, strange fits of mine this past April—and rare, strange fits of Grandfather, too—this strange, maddening April wholly uncharacteristic of both of us)—saw those four years as a life without energy or heart or connection or desire. A life without soul. Dead as that clank of the old Murphy radiator.

Lugging the heavy briefcase still, I squeezed between the empty desks to a high window flung wide open, the blinds raised as high as they could go. I stared down upon the quadrangle and saw, just by chance—a blessing? a curse?—I’ll never know for sure, even now, twenty-six years later—saw a young man, maybe eighteen, walking close beside his girlfriend, their arms curved tightly around each other’s waists. They were dressed in faded blue jeans and tie-dyed T-shirts and floppy leather sandals. They stopped midstride a moment by a great white oak and, embracing softly, tenderly, kissed each other on the mouth—a long, deep, tongue-swirling kiss, the girl sweetly groaning. Then they drew apart, slowly, and the boy reached up to brush a fly from her long dark hair. Then they walked on, slowly, hand in hand, their sandals slapping the brick pavement.

Again, I saw in my mind the grieving girl in the photograph, her mouth wrenched open, crying out the anguish in her young heart, and I felt deep down this Saturday would go different from the others—would have to go different—or I’d take a knife and rip myself open.

Knowing now—but without the words—what it was I first must do, I swung around and strode out of the classroom, kicking aside the close-spaced desks and lugging the black briefcase like a heavy wooden leg I longed to be rid of. I strode down the corridor and through the paired swinging doors and into the vestibule and stopped.

To my right was that other pair of swinging doors—metal gray, scratched everywhere with graffiti, and, as always, unlatched. Taped on the wall to the right of them was a page torn from The Daily Tar Heel, showing Victor’s photograph. I recognized the large head, the high shock of curly hair, the staring eyes and creased forehead, the thick lips—now shut tightly. The headline read, “Student Activists Arrested for Trespassing,” and the article below told how Victor and “a few activist cohorts” had broken into South Building late Wednesday night and “barricaded” themselves inside, “vowing” by megaphone they’d never come out until Chancellor Sitterson had “publicly condemned the Kent State murderers.” But the Chancellor—the article ran on—“refused to accede to the demands of criminals,” and three hours later, the State Patrol was “summoned,” the building “stormed,” and the activists “forcibly evicted.” Going limp, they were “physically carried” to Highway Patrol cars, driven to the Hillsboro jail, and released “on unsecured bond.”

I leaned close to Victor’s photograph and stared at the bulged, bloodshot eyes that, in my bewilderment of the morning, seemed to yell at me: “So you wouldn’t come to our Wednesday rally, prissy, shirking son of a bitch! I know you! Well, girl, since you’re so close now—inches away—maybe you can dredge up the Lockhart guts to enter this thy portal and stride down these thy stair steps and into the shrine you’ve been longing for years to enter and there do the other act that makes you you—what you refuse to admit is in you, a part of you, like your arm, your leg, your ‘unmentionables’ (as you’d prissy-say)—ha!—won’t even admit it to yourself. Yeah, baby, I’ve seen those Blue Boys and muscle mags of yours, sticking out from under your mattress when you hadn’t shoved them in enough. So I know what you want—what you’ve been wanting for fucking years! Besides, I’ve seen the way you stare at me early mornings—yeah, I’m awake as an owl, eyes squinted and just a-suckin’ it all in—pardon the pun, baby. So since you wouldn’t join us Wednesday night and won’t today either—noon to fuckin’ midnight if we have to!—at least long live this revolution—down there—in thy basement shrine of cum and stalls and piss and men. There’s one guy waiting at least—and about your age, too, and just as lonely and hungry as you are—waiting for a suck or a fuck or just a kiss—one deep, deep tounging kiss—so he may as well be yours, baby! And when you’re oh, yeah! satisfied—maybe even cornhole satisfied—then you can dredge up those Lockhart guts to long-leg it down to McCorkle and Franklin and join us and yell!”

Of course, his eyes—his words—were my words speaking to me in my mind, in hushed and frantic whispering: words luring me, hardening me, until I felt a wetness, a slow and sweet-painful ooze. In a clench of fear, I was about to swing around, as I’d swung around many times before, in the late nights I’d finished studying in a Murphy classroom and then left it, breathlessly, and stridden down to the vestibule and caught sight of those swinging, unlatched doors and even pushed through them and stepped—softly, slowly—down the four stair steps, lugging my briefcase, then leaned an ear against another pair of doors, likewise unlatched, gateway to the shrine of my deep heart’s need, and, leaning so, ears as alert and keen as the throbbing in my groin, heard the soft groans and moans, the moist, rhythmic slaps of balls against buttocks, then the louder groans and shrieks of orgasm. How I’d swung around, terror-clenched, and stridden back up the steps and out into the cool, clear night and yelled, “Thank God! Thank God! Thank God!”

So on that Saturday morning, I was just about to swing around again and stride back to the safe serene of my room, gripped in the years-long terror of being myself truly. (Yes, there is ever a terror, a danger, in that—blooming into the man, or woman, wholly different from the person your parents expected, knew, you would turn out to be: the terror because of your new, dizzying freedom and your whole, shuddering openness to the deep, past, scarring wounds in your own—owned—soul.) But then I caught Victor’s eyes again, the bulged, bloodshot eyes in the photograph: saw the rage and passion in them—for acting, living, loving—and I saw once more, in contrast, like a movie in fast forward, my years of stooped head and shirt collars buttoned to the neck and tightly knotted ties and the heavy, black brief briefcase and the solitary studying and all its imprisoning ennui—the isolation, the shame, the death-in-life. And, as if some strange new flame had surged up in me—a flame stranger than all my odd behaviors since this strange, maddening April—a sudden, fierce flame that seemed to pierce from Victor’s eyes, I dropped that grim briefcase like a rock, feeling the floor shudder, and heaved myself through the swinging doors and strode (no stepping “softly, slowly” now) down the four, broad stair steps and shoved through the second pair of swinging doors and into the large, echoing restroom with the six stalls along the left side and the six urinals along the right, the six stained sinks side by side at the far end of the room before me.

The only light filtered in from the four, wide, green-frosted windows above the sinks, windows without latches, not meant to be opened. The light—a dingy, washed-out green—reminded me of the light I had seen in a gas chamber once, when I was ten, and a playmate and I had decided one summer day, on a lark, to dress in suits and ties and catch the bus to south Raleigh and tour Central Prison. The light in the restroom was that same light—sick-green yet oddly alluring.

So quiet it was in that place I felt it was only I there, and I breathed disappointment and relief at the same time. Then I felt so sudden a wave of exhaustion my head swam a little. To steady it, I entered a stall at the far end of the dim room, by one of the stained sinks, quietly lowered the toilet seat and, seeing it was dry, sat on it with my pants still on. I leaned over and cupped my chin in my hand, Thinker-like. For a time I could hear only the sound of my slow breathing—sigh-like, despairing.

Then, in the stall beside me, I heard a footstep, a rustle of cloth, the long, slow rattle of a tissue holder being turned, then the faint rip of the tissue. I stared down to my right just as a thick finger protruded under the stall edge, wrapped thickly in the tissue. As if it were some strange snake charming me, luring me, I rose slowly from my toilet seat and stepped quietly out of the stall and faced the scratched metal door next to mine. I knocked once, gently, shyly, my heart pounding. There was silence a moment inside the stall, then a catch of breath and a belt buckle clinking. Then: the soft, slow sliding down of pants over thighs (jeans, surely—tight ones!), then the elastic band of briefs, the same slow sliding down, paused to be raised over knees, then the continued sliding down—over smooth calves? or hairy ones? I could only wonder. I heard then the quick, rhythmic flicks of a shirt being unbuttoned, then the shirt sliding back over shoulders, down arms, then the soft plop when it hit the tile floor. Then I heard the same smooth sliding of an undershirt being removed and the same little plop.

I squatted and, peering under the door rim, saw thick, black, scuffed hiking boots with thick, white socks mud-stained and folded tightly over the rims of the boots. These would stay on him—how I knew, I didn’t know—I just knew. (Perhaps I knew—I see now—from the Blue Boys from that “bookstore” in east Durham—the slick, musty magazines of grainy photos of “macho” exhibitionists. Yes, long before that Saturday May morning, I’d learned effeminate men weren’t the only ones “that way.” Quite the contrary!)

I stood up, and a latch slid back, sharply, echoing in the large room, and the stall door swung sharply inward, gripped all the way to metal-slap by a meaty, veined hand with thick, flat-tipped fingers and nails trimmed to the quick. The hand was all smooth on the back, not a hair anywhere. It was the huge hand of a wrestler on the team, so it seemed to me then, in my welling fantasy. Through the open door propped by a boot, I saw, even in the dim green of the stall, a crew-cut, heavily muscled guy, about my age, sitting naked on the toilet seat, his thick, shaved thighs spread wide, his thick member erect to his belly button and curving back slightly over the fringe of black hair that ran down, like some dark-alive wire, to his shaved crotch. His arms were raised, spread, elbows bent, into a biceps pose, the defined peaks raised sharp, the inner arms mapped with twisted veins. His chest, all smooth (and, oddly, pale as a sheet) was flexed into twin, slightly quivering mounds with a deep rift down the center of them. The nipples were dark pink and the size of quarters, the center tips raised into hard little cones. His neck was wrestler-thick, and, over his broad, slightly puffy, pimple-cluttered face spread a wide, gap-toothed grin with thick, salmon-colored lips. His eyes—their color invisible—were deep-set under ridged brows, their thick hair meeting above a flat, squashed-in nose. He was a guy right out of the pages of Honcho or Torso or the photo spreads in Blue Boy devoted to wrestling and S & M. For a moment, my head swam, and I thought I was back in my dorm room, alone, the door latched from inside, my eyes peering hungrily at one of those photos. But then the smell—of sharp urine mixed with Clorox—brought me back to the dim green, and I knew this guy was no grainy, fantasy-photo, but sat on that toilet real—solid—absolutely here.

I waited for him to speak, but he kept that wide, gap-toothed smile, that stare under hooded eyes, the thick arms and thick chest flexed and quivering, the member wholly erect and just beginning to ooze from the tip—a tiny, clear bubble that swelled, burst, then slid slowly, in twin curving threads, down the circumcised head.

When the silence and his grinning and the oozing and the flexing became too much to bear—from either of us—I knew (or thought I knew) what it was he wanted me to do—wanted us to do. And so with no words between us, he slid his boot from against the door, and, stepping inside the stall, I turned and closed the door all the way and latched it behind me. Then, facing him, I stepped to him as close as I could and bent my puckered lips to his.

“Naw. No girl stuff!” he yelled, his words like a slap.

I would have swung around and left right then, but I was too “hard” for that—too painful—too welling for him.

Knowing now what he really wanted, I knelt on the cool tile floor and, in surprise to myself (since I’d only read of this “act” before, in those Blue Boys bought, eyes lowered, from that “bookstore” in east Durham), I bent over his erect member and, as if I had done it all my life, gripped its base with my right fist, feeling the rock tautness, the thick, rubbery vein, the sparse stubble of shaved hair. Then I opened my mouth as wide is it could go and, cupping my lips gently around the whole head, tasted the thick rim, the rubbery firmness—smelled the heavy, male-crotch smell. And I began the slow rhythmic sliding I could only imagine, hungrily, for so many years, as I’d waited to burst into white bloom in my bed: my gripping mouth plunging down to shaft-base where my fingers were gently clamped, then sliding back up to the head and coming off it with a loud slurp! Then plunging down again, sucking up again—down and up, down and up, moistening with my spit the whole, hard, curved-back shaft, all the while hearing his low, prolonged groan and then a hoarse, deep “Yeah, oh, yeeeeeee-ah!”

I must have pumped a minute before he came, groaning, in a thick, warm jet on my tongue—a taste sweet, yet slightly astringent, like the smell of a gym or an indoor pool. Suddenly, silent now, he came twice more in my mouth, and I swallowed, savoring each warm, bittersweet burst, while under my fly my own member stood, arcing back—pained, taut, oozing.

“Taste good, yeah!” he whispered, and he reached out a meaty hand and felt my crouch, the bulge and the tautness. “Feels like you’re ready for me, baby!”

I slid my mouth off him and wiped away the single strand of mixed saliva and semen. Then, as if in a dance, we rose at the same time, slowly, gracefully—I from my knees, he from his toilet seat, and he turned around and knelt and pressed the palms of his huge hands tight to the sides of the toilet tank and thrust his rear hard upward. I saw two round, taut glutes, as smooth and pale as the rest of him, and, between the glutes, the darker, hairless cleft of his anus. (Yes, he’d shaved that, too.)

“Don’t worry, baby, I’ve douched,” he said aloud, his voice lilting suddenly, girl-like, on the “douched.”

I saw that dark crevice of his anus inviting me, and, from my years of Blue Boys, from my recent weeks of intent listening outside the restroom doors—to the breathy groans, the rhythmic slapping of balls against buttocks—I knew, once more, exactly what to do: how to perform the whole lust-crazed, and, at that time in my life, shamefully relished ritual.

Quickly, breathlessly, I unbuckled my belt and shoved down pants and underwear to my shoes. Three or four times I fingered saliva off my tongue and onto my cock, spreading it thick around the taut head and down the shaft, and then, kneeling again and gripping it, I began to slide it slowly into him. I heard his breath catch, and I whispered, “Slower? Am I hurting you?” And he cried out, in pain, “No! Fuck me hard, baby! Make me bleed!”

I pushed all the way in, felt the soft-hard doughnut in him that kept me from going deeper, heard him shriek, “Aw yeeeeeee-ah!”—and cried out myself, “Oh, God, Jesus!” all the while wondering in my mind, Is this I—here, now, doing this, yelling this?

I could not recognize myself. This couldn’t be I. And for a moment I felt as if I, the real I, were standing back against the stall door, watching the whole scene, dispassionately, my elbows folded: two young men—one tall and lanky, the other his thick and muscular opposite—fucking like dogs, or, to put it literarily, performing the sodomy to which Dante assigned a whole circle of Hell, a whole ring of Purgatory.

And then I—this not-I, this not-Lockhart Elledge—must have shed, slid off, shook loose—I don’t know how to say it—all those celibate, armored, held-in years like layer upon layer of old numbed and leathered skin. For, like a seasoned yet still hungry lover, I leaned upon his broad back ridged with muscle, clamped my skinny arms around his thick shoulders, felt in my elbows’ hollows the hard, bunched curves of his deltoids: yes, I clamped—hugged—him so hard I trembled, and began to pump into him as hard as I could, in and back, in and back, in and back, taking care to stay in him, never slide out of him. (“Seasoned yet hungry”—there were no other words.)

I bent my head down and around him, saw his meaty grip pumping his own member, grown stiff again, and after I’d pumped a minute maybe, I came in a huge relieving burst, filling him full (or so it seemed, in my wild fantasy), and right after, thick jets of white flew out of him, splattering the toilet bowl.

While he groaned loudly, echoing in the vast room, I kept silent, thinking—no, longing—it would happen: Yes, he—the old fart—he’s come to the swinging doors now, seeking me here, knowing, somehow, exactly where he’ll find me and what I’ll be doing, and now he’s pushing himself slowly, weakly through the swinging doors and entering the vast, urine-smelling room, stopping a moment to adjust old eyes to the dim green. He steps forward now, slowly, in his old man’s listing gait. He steps, knowing, to the next-to-last stall from the row of sinks. Now, with a veined hand, he pushes the stall door, but it won’t open, so he leans his spider-veined face to a slit between the door hinges, and, yes, even with his old eyes, squinting till they tear, he sees me inside—me, his only grandson, the Professor Classicus Futurus, the family scion of “highest hopes” and “limitless expectations” (as he wrote me on a postcard once—years ago). Yes, the stuck-up old fart, he sees me, this “scion,” now kneeling on dirty semen-stained tile, locked inside the bowels of some “common,” pea-brained athlete, my arms tight as a lover’s—a pervert’s, rather—around the crudely overpumped shoulders—me, the sole, fertile male “sustainer” of the Woodall line, pumping his last, thick, white burst as crudely as one dog into another, while the crude, “common,” pea-brained athlete cries out, “Fuck me hard, baby! Make me bleed!”

(But, of course, the old man never enters this dim green and never will. He now stands erect and elegant beside the Old Well, old, watery blue eyes fixed across Cameron and down the wide, brick walkway, waiting . . . )

When I filled the wrestler all I could, I felt at once the old emptiness and melancholy after orgasm, then the old, filling shame, and I thought, angrily, No, Lock, you’re not that. You should know better! You’re better than that! How I hate that! It’s not your direction! Can’t you realize? Can’t you learn? Just like your whoring father—never could learn!—and shot dead in a Phenix City whorehouse before you were born or when I was just a baby two years old, I can’t remember! (And I couldn’t remember, not then.)

I slid out of him, quickly, and without even wiping the shit off me, I stood and jerked up my underwear and dress pants and buckled my belt and swung around and unlatched the door and rushed out of the stall. As I strode to the swinging doors, I heard him shout, “Hey, what’s the rush, darlin’? You’re good, baby! Nice big dick! But you got to learn to hold it longer—fuck me till I bleed! So how ’bout tonight? Say nine? Same place? Same stall? I’ll be waitin’ on yuh, pumpin’ for yuh. And maybe we’ll do the girl-stuff. Your lips—they pretty sexy, too!”

He went on longer—hoarsely, longingly, desperately (or so it seemed to me then)—but I could no longer hear him, since I’d left that dirty, urine-stinking room, that dim, nauseous green which—especially now, fiercely—called to mind the gas chamber I had seen when I was ten and dressed in a suit, in the summertime.

Beyond the second pair of doors I gripped up the heavy, black briefcase and strode out of the vestibule and into the sunny air, shoving all that pervert- stuff—that not-Lockhart Elledge—behind me.

But when I came within sight of the Playmakers and saw, in the oak-shaded distance, my Grandfather Woodall standing beside the Old Well, peering just now at his big pocket watch, I tasted the sticky semen on the roof of my mouth, smelled the vile shit welling up out of my crotch and the sharp sweat from my perverted exertions, saw the new ragged wrinkles and creases in my newly pressed pants and starched shirt, and I knew I could not go meet him now and grip his proffered hand—not in this dishevelment—this not-me.

So I sneaked—there’s no other word—around the other end of the Playmakers, the portico end, and entered Old East by a side door and strode up the three flights of stairway and into my room and shut the door behind me. I dropped the briefcase on the bed and went to the shut window before my desk and looked down at the Old Well and saw him standing beside it, gray Homburg held out with both veined hands in front of him, his blue gaze fixed across Cameron at the brick walkway between South Building and the Playmakers Theater. Seeing him so erect and elegant there, the sun just now glowing him full, from his silver crown to the shining black tips of his shoes—and remembering, too, how it had gone between us every Saturday morning since the twenty-eighth of March—the whole blessed, because expected, ritual!—and wanting—longing—that it should come round so again, I saw it was five before nine by the clock on my desk, and I thought, Yes, if I hurried, I’d have time to shower and change clothes and rinse my mouth and go out the side door and come around the Playmakers and stride to him, carrying the heavy briefcase—I, the Lockhart-Titus-Elledge-Classics-Man he’s always known me to be (for four years anyway)—my right hand, as I’ll approach him, stretched out to grip his proffered one. So—yes—I can still make it all come round again, and it’ll be as if all that—in that sick-green restroom—never happened—all that “pervert stuff.” (So I called it then, twenty-six years ago, in my innocence, my ignorance).

But, again, I tasted the semen, felt it sticky and sordid on my palate, like rotten glue, and, again, I smelled the shit welling in sharp waves from out of my crotch, and I remembered that girl in the photograph, her mouth wrenched wide in grief, remembered the empty campus and the canceled class and Dr. Applewhite’s neat cursive on the blackboard, remembered the big peace rally planned for tonight: knew McCorkle Place was already being filled with herds of long-haired, patches-jeaned “peaceniks” and leather-goods hawkers and ponytailed technicians setting up podiums and speakers and amplifiers and microphones and the white, portable toilets that, even empty, always seemed to spread their stink of urine. And I knew at noon Grandfather and I, in our dress clothes and ties, would have to cross that noisy, smelly quadrangle on our way to Harry’s and then cross it again on our way back, Grandfather to his old Chrysler, I to my dorm room in Old East. And I knew that night even my shut windows could not muffle the vulgar rock music from even as far away as McCorkle—could not muffle the harsh ranting of the speakers and the ugly cheers and the insipid slogan so popular since a recent speech of Nixon’s—that vulgar chant and response: “What do we want? [Pause.] PEACE!” [Pause.] “When do we want it?” [Pause.] NOW!”

And I knew, my mind still cluttered by the daylong distraction—and, yes, my shame still lingering from the morning hour in the Murphy Hall restroom—I’d rise irritably from the Fourth Georgic now and again all through the noisy evening and sweating miserably in the overwarm room, pace about, fingers in ears, and shout, “Shut up! Shut up! Shut up, faggots!” And then, oddly, to calm myself, I knew I’d step, ears still plugged, to the window above my bed, shut tight, like the other, and leaning sideways, stare down on the pinewood of the sill and read once more the mysterious graffiti—the “inscription,” rather—carved carefully, it seemed, by a small pocket knife: that “CARPE DIEM, QUAM MINIMUM CREDULA POSTERO. BUT NOT FOR ME. NOT ANY MORE. NEVER. NEVER. NEVER. NEVER. I THINK IT’S FIVE. I’LL ADD ANOTHER. NEVER. 8 MAY 19—” For four years nearly, I’d often wondered about it: Who’d carved it? And why so carefully? It must have taken him hours. And what was he thinking—feeling? In what year was it carved? It looked old, was all I could surmise from the faded and shallow cuts of the high, neat, perfectly aligned all-capitals, polished over by the years—decades!—of janitors. (Victor never noticed it, and I never brought it to his attention. It was my odd, private prayer, meant for my eyes only—and for some deep, unknown place in my soul.)

And I knew that at nine that night the wrestler would be awaiting me, tempting me, naked on his toilet seat, in that dim-green death chamber in the basement of Murphy Hall.

Remembering—and foreseeing—all this prickly and black disorder distorting my for so long serene and bright and studious Saturdays, I realized, with a breath-clench of fear, that I could not stay in this room today and sit all daylight and into the night (perhaps grabbing a bite at Lenoir) before my open Fourth Georgic and translate those suddenly tiresome lines, all the while tasting the residue of that common hunk’s semen in my mouth which I knew would take hours to clear, no matter how often I’d rise to go out to the restroom and rinse and gargle. No, in fact, I wouldn’t—couldn’t—stay anywhere else on campus or even in town.

But where would I go—escape? I dreaded a bus ride or a hitchhike home (where, since my last visit on March 21, a Saturday, I had decided never to visit again, except for Thanksgiving and Christmas and Easter and birthdays—and only then to satisfy my mother’s constant pleading—“for my sake,” she had whined, “and for the family.”) In fact, ever since that Saturday, just the thought of home—the being there—depressed me: my always slightly chill upstairs bedroom, my Georgics open on the rickety, fake-pine, little-boy’s desk by the red-curtained window—desk and curtains I had known, in the despair of familiarity, since I was five or six.

So—Where? Where? I flailed inwardly.

My eyes on Grandfather glowing in full sun now, like a classic statue, I saw in my mind, at first in far, aching distance, at the beginning of a long, straight, dirt drive flanked by tall pines, the sunlit, white façade of an antebellum house, the middle third of it a double portico of balustrades and four Ionic columns. Under a green, low-pitched roof shone a triangular pediment with a little arched window in the center—a third eye, if you will, winking back the sun. As I came closer, I saw, near the left end of the portico, a huge, old oak in full leaf, its thick branches arcing over the drive. A white-brick chimney stood high at each corner of the great house. Closer still, I saw the large upper and lower double windows on each side of the porticos, their green shutters now attached, but closed. And I saw, in the center of the lower portico, the broad, white, intricately molded double door, just now opening inward, inviting me . . .

I saw a great serenity in that place I had nearly forgotten ever was, and, with its white-glowing image in my mind, its façade nearly like that of a temple at Paestum or Delphi, I saw a refuge—a soul restorative—where just by breathing of the pine-winey floorboards and the remnant leaves of tobacco hung every September in one of the upper rooms, I could cleanse away all my sick-green shame and black distraction of the morning. And I decided that this Saturday I’d at last, like some long-withholding lover, surrender myself and, hard upon our ritual grip, say—cry out even, like a breathless boy: “Yes, Grandfather, I’ll drive down with you today. We can stop by Bentonville and tour the battlefield and then visit Mrs. Wooten in Rosewood and then meet Uncle Merrick on the lower portico, and when the papers are signed and you own your dream (or nearly own it) [I knew the closing might take weeks to complete], we can stop by Ava Gardner’s school—I’ve never seen it—the inside of it—and, if we have the time, that old church your grandfather Blow-Your-Horn-Billy built for the colored people—I’ve never seen it either—the inside.” (I had seen the interior—but just once—and the ten years since had damped the episode from memory—to which I’ll come in due time.)

So I had planned to say to him, in a relieving, longing burst. But first I had to clean myself—shower and scrub—then change into clean, pressed dress slacks and starched white shirt and tie, had to rinse and gargle as hard as I could.

I hurried through all of it—so fast I forgot to pack laundry and clean clothes, forgot even my books and briefcase. In ten minutes, I was down the stairs and out the front door, walking slowly and quietly toward him, arms swinging loosely. I came up behind him, not quite on tiptoe, and said right out not the long, boyishly breathless speech I’d planned—wanted—but the simple, almost perfunctory, “Dee-di, does Uncle Merrick know we’re on our way?” (“Dee-di”—this was the first time I’d called him that since I was twelve. For years—the few times I’d seen him—I’d addressed him as “Grandfather,” even to his face, or, jocularly, as “Dr. Claude Alexander Woodall, Medical Man.”)

He gave a little jerk of surprise and turned around, listing slightly, and faced me and, holding his Homburg in his left hand, stretched out his right. I gripped it, dutifully, and then, as he set the Homburg on his head, straightening it just so, his face began to flush with pleasure, and his eyes brightened behind the thick glasses, and he said, in his old voice laced with catarrh, “So you’ve at last received a break in your hard studying, Dr. Lockhart—but—why—you’re supposed to—” He waved a veined hand back toward South Building and the Playmakers, my usual route to him.

“My class was canceled,” I said. “You know—all the peace people and that sort of thing.”

He nodded, chuckling, “Yessir,” and, tapping his foot in rhythm, softly chanted, “‘All we want is peace, peace, peace.’” Then he laughed, “Heh heh, all that carrying on.” I laughed with him, conspiratorially: all that common, herd behavior was beneath us.

Then he cleared his throat and said, “My car’s in the Playmakers lot. We can be down in Klan Country in an hour and a half.” Here he laughed at some private joke and whispered, just loud enough for me to hear, “Yessir, your old Uncle Merrick, he was one of ’em, maybe still is.”

II

My grandfather and I entered the Chrysler and shut our doors, and I felt at once the close, stale heat of the old car (a ’62), and, with the heat, as if woven into it, the warm, thick odor—partly of sweat, partly of mothballs and dry cleaning fluid, partly the indefinable smell of old male bodies: a smell I remembered from years ago—from his paired bedroom closets back in Raleigh.

With a hoarse “Whew!” he rolled his window down, and I rolled down mine, and as we swung out of the parking lot and drove up past Forest Theater toward Raleigh Road, a rushing breeze took all that heat away.

But the smell lingered—that multitudinous smell, holding in my mind some cramped and cramping memory. I strained to name it—to picture it—but before it could come clear in my mind, we had already left town—had, in fact, come off the long, downhill divided highway and onto the narrow, flat two-laner. And he, my Grandfather Woodall, his face flushed with a sudden, manic nostalgia, had begun to speak, a veined hand gesturing now and again at the roadsides flanked by thick pines and scrub oaks stringed lush with kudzu. He was speaking of May 1909:

“Yessir, exactly May, maybe this very date, and a Saturday, too, like now, about nine—clear and sunny, cool-warm as June. The night before, my two Kappa Sigma buddies and I had just taken a notion, ‘Hey, let’s walk to Nelson tomorrow and catch the noon train to Goldsboro. We can be home by nightfall.’ (We didn’t even think to hitchhike—we wanted the walk, young folks we were back then.) So with knapsacks of books and clothes strapped to our shoulders, we started out next day, Saturday, just now, striding fast along the roadside to get to Nelson by noon. ’Course, the nine miles was dirt then, and single-lane, the pines and scrub oaks thick up to the road edge—no grassy shoulders in those days, nosir. Every so often a Model T’d chug by, coating us in dust. Lord, we patted and brushed until our shoulders hurt! We walked fast, like I said—long-striding—’cause we knew the train left Nelson at noon. We’d found out that much ahead of time, anyway. All we could hear—’cept for the T’s passing about every half hour—were our own pounding strides and now and then a jay-squawk and the mourning doves woo-woo-wu-wooing, you know how they do—“tua cura, palumbes,” as old Maro coos it. But that was all: it was that quiet, 1909-quiet. And the more we strode and the faster we strode, the more we felt like striding—Lord, we could stride on forever in those years! Don’t ever get old, Dr. Lockhart. Don’t ever get old.”

He went silent a moment, and the smell struck me again, the shrouding old-man part of it that I remembered from his double closets years ago.

He cleared his throat long and deep and rasped on: “So sure enough, a minute before noon, we arrived at Nelson—just a little, tin-roofed platform by the single track, and beside it a sign, “Nelson,” on a stake stuck in the ground. Lord, we were just in time, hearing the old steam engine whistling a half mile away, and in a minute its squeal and clatter and long shrill of steam as it pulled up by the platform and stopped.”

He went silent again as we passed under the railroad bridge and stopped at an intersection. A few yards to our left stood a small, “official,” rectangular sign on a creosote post driven into bare clay: NELSON—black capitals on white, rust-edged metal. Beyond the sign I saw no covered platform where a train might stop—just the glittering metal of a single railroad track high on a clay embankment covered with weeds and crabgrass. Across the highway stood four, identical Carolina-T farmhouses spaced far apart, weather-blackened, their front windows broken out, beer cans and cellophane wrappers scattered over the sagging and stepless front porches. I squinted at the glittering rails and pictured that little, tin-roofed platform and the three knapsacked young men leaping onto it in their loose-fitting, long-sleeved, coarse, cotton shirts and their berets and tan breeches and brown knee socks and black brogans, their young faces flushed to beet-color from the nine-mile hike. And in my grandfather’s silence, I caught that smell again—now the astringent, mixed sweat and dry cleaning fluid and then, suddenly, a new smell: the harsh soap, nearly like lye, that he must have used as a boy and a young man and all through his middle age—soap he was showering with even now, at eighty-one.

He jerked his head to the left, then swung right, and we were driving the two-lane road that continued 54. We rode in silence awhile, following the railroad atop the high, weedy, clay-patched embankment.

“What’re you thinking of, Dr. Lockhart?” Grandfather broke suddenly, clearing his throat.

I tasted the wrestler-hunk’s semen still sticking to the roof of my mouth and so thought of him and the dim-green restroom and tonight and nine o’clock.

But I said, to damp the taste, the sudden shame (and unaware of my pun), “Oh, just Nelson. It isn’t much, is it?”

He whispered a hoarse “heh heh” and said, “Nosir, wasn’t much in ought nine, either. Just those same old Carolina T’s, but newer, painted, and with folks living in them. Those and the tin-roofed platform by the tracks. Up till ’45 even, you could see young men in threes or fours striding out the nine miles from the Hill to catch the train headed east. (Now the Greensboro and Winston and Asheville boys had it easy—just a miler into Carrboro— University Station.) The shed here’s gone now, of course—dismantled in ’46 when 54 was paved at last and the boys could catch rides in a minute, or the post-War boom gave their fathers money to buy ’em cars. The Southern Railway people didn’t see any use in keeping it.”

He went silent again and after a mile maybe, began whispering to himself, his thin, pale-pruned lips faintly twitching. Every so often I’d hear, “Yessir, I should’ve told that fellah where to head in,” punctuated, oddly, with a faint “heh heh.” He was far away from me now—only his smell lingering: those complications of smells.

Suddenly the smells brought back, clear as on a movie screen, that cramped and cramping memory. It was a day in mid-May 1966, a Saturday, to be sure—the day I last rode with him into “Klan Country” and the old Woodall homeplace. I recall it so vividly because it was the day—on our way back to Raleigh in late afternoon, just as we left Smithfield and crossed the Neuse River Bridge, passed the huge billboard that faced drivers entering town, the billboard of crudely painted men shrouded in white gowns and hoods and holding aloft fiery torches, and, beneath the ugly figures, the hand-printed WELCOME TO JOHNSTON COUNTY! THIS IS KLAN COUNTRY!—that I announced to him I was “cured at last” of my “inversion”—my “mental illness,” at least as far as Dr. Aldred “was concerned.” And to prove I was “cured,” I told him I was “escorting” a “Linda Fuller” to the Senior Prom on the last Saturday in May. She was “a respectable girl” (so I assured him)—a girl of “good family.” In fact, she lived on White Oak Road, his street, though “residing” on the block near Five Points, which, as he knew, was a “more modest” section than his, with its nearly identical ’40s bungalows all crowded together on narrow lots. Still, it was White Oak Road, and he knew what that meant: junior college at St. Mary’s, the last two years at Hollins or Sweet Briar, a trip to Europe after graduation, and her “debut” at Memorial Auditorium in June of her twenty-third year.

* * * * * *

At noon that last Saturday (I remembered), Grandfather had showed up at our house and invited me “for a short drive, Mr. Lockhart Titus—to give you a break from your hard studying.” I did need the break, and I was curious about Grandfather’s sudden, and unexpected, invitation. (He usually telephoned ahead if he was to drive me anywhere.) So I climbed into the old Chrysler, and we headed downtown.

On the way, he rasped, “Since tonight, Mr. Lockhart Titus, you shall be escorting that respectable girl, Miss Linda Fuller, to the site of your Senior Promenade and since it is an old custom that in such circumstances, the male do the driving, it is my intention to present you with an afternoon’s worth of lessons.”

Before the Prom, I had not considered that “old custom”—and I shuddered inwardly at the prospect of “an afternoon’s worth of lessons.” For a complication of reasons I could not then account for, driving had long terrified me, and I had wanted to postpone learning it as long as I could. So in the hope (in vain, as it turned out) that Grandfather would take me back home, I blurted out, “But I don’t have a license! Or even a learner’s permit!”

“A license or permit shall not be necessary for this occasion, Mr. Lockhart Titus,” he rasped. “You shall be driving but a short distance and with barely an ounce of champagne in your system, if that, and I am sure that after my lessons today, you shall drive with such exceeding care that no police officer shall even think of pulling you over. And besides, do you intend for Miss Fuller to drive you? Or myself? Or even your mother?”

The mere thought of any of them in the driver’s seat on the way to this prom—the proof that I “was cured at last” of my “inversion,” my “mental illness”—chilled me more than the prospect of driving. So seeing no way out of my dilemma, I faked a smile, slapped the dashboard, and joked loudly (remembering a race car magazine I had seen on our coffee table, left behind by one of Mother’s old boyfriends), “Let’s floor this old rod, Cale Yarborough!”

We both laughed, and in a minute we arrived at a large, vacant parking lot beside the State Board of Health, changed seats, and began the lesson. The rest of the afternoon, to Grandfather’s patient advice, I practiced punching those old ’62 Chrysler buttons for Forward and Park and Reverse, accelerating smoothly, backing up (my head twisted around, my right arm stretched out over the top of the front seat, my eyes remaining steady on the asphalt behind me until the old car stopped completely), using the parking brake, making the “quick stop” for emergencies—and more. Grandfather even had me drive around the block (the streets mostly empty on Saturday, when few State employees came to work) so that I could practice the hand signals, turning right and left, and, at stop signs, coming to a “complete stop, Mr. Lockhart Titus.”

* * * * * *

These Klan Country “excursions into history,” as Grandfather called them, were taken every Saturday—including the summer ones—from May ’65 to May ’66, and were an unspoken corequisite of my “therapy” with Dr. Aldred: these afternoon ritual journeys down to the Bentonville Battleground, the old Woodall homeplace, the now-abandoned red-brick schoolhouse where Ava Gardner had been taught, the white clapboard teacherage beside it (where Ava and her family had served the Brogden teachers in the twenties and thirties), and, finally, the old white clapboard church, never locked, ever shuttered, that my great-great-grandfather, Unionist Blow-Your-Horn Billy Woodall, had built “for the colored people,” just a year past “the Surrender.”

My grandfather and I would stop before these “shrines” (as he’d call them, laughing softly)—and without ever walking the battleground (we’d just park before the Harper House and watch it for a time), and without ever setting foot in the schoolhouse or the teacherage or even in the homeplace or the old colored church, just standing outside of them in raw cold in January or sweating heat in July—he’d recount some long, digressive anecdote linked to the “shrine,” a tale ending always with some homily about my Southern “roots” nourished by “tragic devotion to a lost cause,” about the “people” I “came from” and their “integrity” and “honor” and, in my great-great-grandfather’s case, their “unsparing generosity to those less fortunate.” In front of Ava Gardner’s school, he’d speak, his face as flushed as a teenager’s in love, about “the lady”—“the beauty”—who had sprung from the Woodall “homeland” and who graced it even now—in the memory of her teacher, my great-aunt Venice, in one of the classrooms in the old Brogden schoolhouse, and in that abandoned teacherage beside it.

Just as we started the drive back to Raleigh, he would clear his throat and speak, as if in peroration, of my ancestors’ “fulfilled and fulfilling roles as dutiful parents of upright and virtuous children.” These “visitations,” if you will, along with my thrice-a-week “talk-and-aversion” sessions with Dr. Aldred, were intended to return me to “normalcy”: the “condition” of a red-blooded but “intellectual” Southern young man of the higher class, who, in his late twenties or early thirties, after he’d received his doctorate, summa cum laude, in Latin and Greek, would “settle down” in Chapel Hill or at Duke and marry a “goodly lady of like background” who would bear him two or three children (preferably male) to carry on the Woodall line for yet another generation—“at least on the distaff side.”

(Of course, Grandfather would vocally underscore distaff since he knew as well as I that I was named in toto after my father, Lockhart Titus Elledge, Sr.—my dead, “deadbeat,” “no ’count” father who, under mysterious circumstances, had been stabbed to death—so it was rumored—in a sleazy whorehouse in Phenix City, Alabama, three months before I and my twin Lucinda were born. To Mother, the word distaff never entered her head—not because she didn’t know what it meant, but because, to her, I was a Woodall now, through and through, and would remain a Woodall forevermore—despite the obvious high cheekbones and prominent jawline and dimpled chin my father’s “fatal” sperm had bequeathed me. In fact, Mother—so she claimed, again and again—would have changed her last name back to her maiden one, except that for a decade, she had written news articles and a daily column as “Joan Elledge” for a local newspaper and for three years now, had hosted a morning cooking-and-interview show, Femme Fare with Joan Elledge, on local television.)

As for this “inversion” of mine (what Dr. Aldred termed it), Grandfather and I had recognized it much earlier, when I was twelve—but we kept it a secret, not even mentioning between us. In fact, it was never revealed in the clear light of family until an “incident” (all Mother and Grandfather ever called it—the “unsavory” details they never uttered aloud) that happened when I was seventeen and nearing the end of my junior year at Broughton High.

I was an actor in the Golden Masquers, and, because I was tall and my voice deep, I had been assigned the role of Cothurnus in a Millay one-act, Aria da Capo. Oddly—given my twenty-six years in theater at forty-eight—I recall little of the part and even less of the play, but I do remember—even now, nearly three decades later—the piercing mildew of the thin mattress (discarded from who knew where!) that lay folded in a corner of the narrow backstage. And I remember how the whole of that April, Monday through Friday, he and I would spread that mattress onto the splintered and pitted stage floor, moving in slow and, oh, so acheful silence, though it was 4:30 in the afternoon and rehearsals were done and for a half hour (until the janitors would arrive), we had the whole echoing auditorium to ourselves.

Did I say “he and I” and not “she and I”?

His name was Kenny Vaughn. He was sixteen, an October boy and so a few months younger than I. Since September, the Masquers had performed Anastasia, Dust of the Road, You Can’t Take It With You, and now, in April, had begun rehearsals for Aria. I first saw him when he showed up at the tryouts for Anastasia and spoke the lines for Prince Paul in a delivery so monotonous, so halting and stumbling—like a child learning aloud The Pledge of Allegiance—that Mrs. Peacock, after allowing him to finish, smiled Southern-lady-gracious and said, “Thank you so much, Kenny. We’ll be in touch. Next, please. Yes—Jean Watson—Anna-Anastasia herself!”

But because Kenny was broad-shouldered and tall for his age (taller than I even), and took “shop,” Mrs. Peacock sent him a note the next day, to his homeroom, asking him to “TAKE COMPLETE CHARGE OF THE STAGE CREW—FOR ALL OUR PRODUCTIONS.” (Yes, she capped the whole request, knowing it would make Kenny proud—especially since he’d know he’d be ALL the crew in our smaller productions and in charge of two or three crew members in our larger ones.)

And just as she must have expected, the very same day, Kenny rushed into her classroom at half past three and, even when some students were present, blurted out breathlessly, “Wow, like thanks, Mizz Peacock! Like—you can’t imagine! Oh, wow, I’ll be there every day—come in Saturdays, too—for the props and everything!”

(Yes, he was that open, that innocent—the naïf among us Masquers “sophisticates.”) And every Monday-through-Friday for the several weeks of rehearsals following, at precisely 3:30 in the afternoon, he’d jog, arms pumping, down the middle aisle of the auditorium and, ignoring the stage steps, slap, palm-down, broad, thick-fingered hands onto the stage floor and push himself up onto it, as gracefully as a gymnast, and then turn and face us in our seats, and, grinning broadly, his freckled face flushed with pleasure, bow low before us, forearm tight over his waist, as he’d hear our delighted applause. (We Broughton “sophisticates” all loved Kenny, in that slightly patronizing way we “loved” someone physically crippled or mentally “deficient.”) He’d be changed from his J. C. Penney’s button-down shirt and polished-cotton slacks and black loafers into ragged, dirt-stained sneakers, faded blue jeans, and a torn, white T-shirt with the tail out and worn thin from repeated washing. I’d be sitting in the front row (of course!), and glancing up from my lines—of the raging Count in Anastasia and, later, of the mournful tramp in Dust, of the stuffed-shirt Mr. Kirby in the Hart-Kaufman play, and now, in April, of somber Cothurnus in Aria—I’d notice, right away, as he scrambled onto the stage and turned and bowed and rose again, the startling blue eyes and the light brown hair tousled over his forehead, the sinewy forearms with the veins showing, the jeans tight as skin against his crotch and round firm butt, the T-shirt tears that showed the sinewy ridges of his freckled shoulders.

And when his blue eyes would meet mine (and, yes, they always would, every time I’d glance up at him), I’d quick-bend down at my angry or mourning or stuffed-shirt or somber lines and, tingling red with shame, feel myself harden under my fly—a sudden, startling rock-hardening, like a fist striking me pleasurably, down there.

It began, this “incident” between us, on an April Fool’s afternoon, when, on a sudden whim strange to me—a not-me—I waited until the other actors and Mrs. Peacock and few spectators (mostly parents) had left the auditorium, and I stepped up to the stage and without a word to him, just started lifting one prop after another and lugging it backstage. He did the same, without a word to me either, and helped me move the larger props and the big flats, glancing at me now and again, a blue eye of his winking at me, sly and conspiratorial (or so I saw it then—my not-Lockhart Elledge). After we swept the stage floor, our chores were done, and in the echoing auditorium, we sat close beside each other, stage-edge, our legs dangling down. We’re just resting, part of me thought—the real me—but that other I—the not-I—felt dry in my mouth and shivered pleasurably and wondered, Will he kiss me? Or should I start it? I remember his sudden turning, as if he were reading my mind, and then his leaning over and his sudden, startling kiss on my mouth, and then, without thinking, my kiss in return, my tongue relishing his thick lips, parting them, relishing his warm tongue, and then his tongue swirling, relishing mine.

The Thursday following, we discovered the mattress, and to our deep delight, no longer having to sit, we rolled it out to mid-stage. After Kenny, grinning, focused a deep red spotlight on it, we fairly plunged upon its cool mustiness and began, wildly, passionately, the embracing, the caressing, the rubbing of our shoulders, arms, calves, thighs, the thick, hard bulges in our pants (his tight blue jeans, my loose khakis.) Then we kissed and kissed and kissed each other until our upper lips were bruised—purple-red as raspberries in the long, cracked mirror backstage.

By mid-April, we had shoved off our clothes (having latched the doors to the wings and backstage and fastened together the closed stage curtains with three, large safety pins) and had begun the bare-skin fondling, the cuddling, and that other kind of rubbing—the frottage, if you will. For one shining hour of a Friday, we tasted each other, simultaneously: his cock long and thin, sweetly bitter with his smegma (he wasn’t circumcised), mine short, fat, bald—and smelling (so he moaned) “like sweet chlorine.” By the last Thursday of April, after so many awkward—and painful—failures, we at last entered each other and bloomed inside—me into him, then him into me.

It was during our final “cornhole” (so he crudely called it—I preferred “Uranian bliss,” poetaster that I was in those days) when we were caught. A janitor—a tiny, shriveled, old white man, the only white among the rest of them—and a zealous Southern Baptist to boot—happened to arrive around fifteen minutes early that afternoon—the last day of April, a Friday, I remember the day exactly. He must have seen the stage curtains awry and stepped closer, on tiptoe likely—he was that quiet. Then, seeing the three large safety pins and knowing “somethin’ won’t quite right” (as he must have told Mr. Holliday Monday morning), he quietly unfastened them, one by one, set them quietly on the stage rim, and gimped through the parted curtains. Before Kenny and I could uncouple, he saw, center stage, on the mattress lit by the red spotlight, my legs thrown back over my shoulders and then our two naked butts, Kenny’s above mine and so tightly joined they looked like one taut moon of flesh. As Kenny groaned with his orgasm inside me, I remember shouting—even as I saw Mr. Whipple standing over us, jowls red and quivering, “God, Kenny, I love you so! Fill me full!” and then, my right hand pumping furiously, I streamed out my own white bloom into the cleft of Kenny’s molded chest.

I don’t remember the details of what happened next—just a shameful parting: Kenny dressing quickly and, nearly tearing the lever off it, rushing out the exit door—my last sight of him, ever—and I, suffused with shame, guilt, and sweet recollection, all at the same time, stretched naked on my back, on the thin smelly mattress, sweating in the red spotlight, hearing old Mr. Whipple gimp down the stage steps and up the auditorium aisle, all the while muttering to himself—curses? prayers?—I could not hear to tell.

Monday afternoon, I arrived promptly at 3:30 in the cramped, overwarm principal’s office while Mother and Mr. Holliday were already “conferring.” The office reeked of pipe tobacco, and Mr. Holliday had his pipe’s stem-end clenched in the corner of his mouth. After asking me to “sit, please, Lockhart,” in a wooden school desk across from the two of them, he told me Mr. Whipple had come to his office “first thing” in the morning and reported my “sordid and indecent act” and knowing “Kenny’s daddy” (from Hayes-Barton Baptist), had already phoned him and told him about it. “Of course,” Kenny had “confessed on the spot,” and Mr. Vaughn had “removed” him from Broughton for the rest of the school year—“for reasons of ill health.” And he had “made arrangements” for Kenny to attend a military academy in South Carolina, starting in the summer. The school had a reputation for “straightening out troubled youngsters.”